The use of continuous tracks as a system of vehicle propulsion has a long history, stemming back all the way to the 1820s and ’30s. Initially created as a means to better distribute the weight of heavy vehicles compared with steel or rubber tires, tracked vehicles could traverse soft ground with a reduced risk of sinking and becoming stuck. Today, advancement in continuous tracks continue at pace, and a relatively new form looks to offer an extended lifecycle and reduced maintenance time and costs.

Back at the start of things, continuous track took the form of a solid chain track made of steel plates with or without rubber pads, which is still commonly used today for heavy construction and military vehicles. For these steel tracks (ST), the advantages they possessed over rubber tires in terms of durability and ruggedness were key factors in driving its adoption – the prominent treads of the metal plates were far more hard-wearing and damage resistant, and the improved weight distribution reduced wear and tear on different parts of the vehicle, enhancing both its performance and lifecycle.

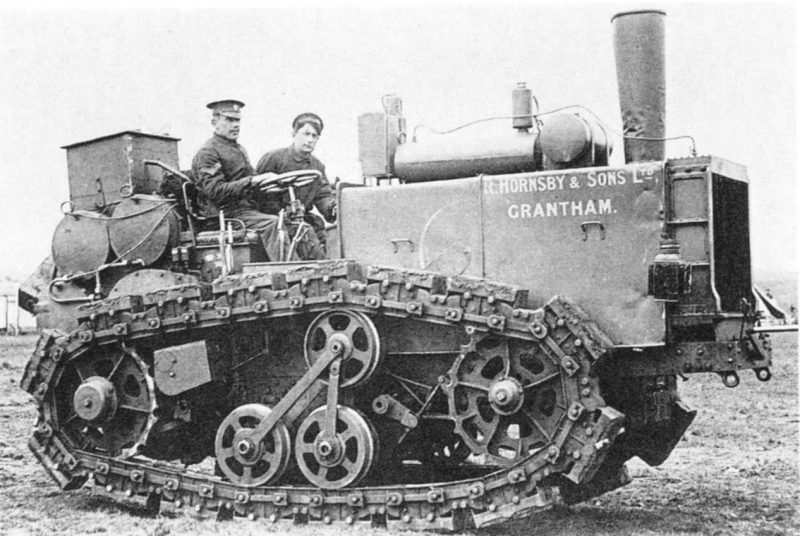

With this in mind, it wasn’t long before militaries around the world began looking into the benefits of ST. In 1905, the British agricultural company Hornsby & Sons, patented one of the first continuous tracks for agricultural tractors. The British Army would trial its tracks for artillery tractors on several occasions between 1905–1910, though continuous track wouldn’t officially be applied to a military vehicle until the British prototype tank ‘Little Willie’, constructed in 1915.

From there, the First World War did much to drive the adaption of ST, as the British and Austro-Hungarian armies made use of Holt tractors to tow heavy artillery – once more, agricultural vehicles paving the way. The first tanks to enter the war, the UK’s ‘Mark I’, were inspired by those Holt tractors – and soon after, both France and Germany would introduce tanks built on modified Holt running gear.

Time for a change

Ever since, ST has held the pole position as the traditional choice for armoured fighting vehicles, though this is starting to change. Many manufacturers have now turned to composite rubber tracks (CRT) instead of steel. Rather than a track made of linked steel plates, CRT consists of a synthetic rubber belt with chevron treads reinforced with steel wires. A complex and composite material, CRT offers a number of advantages over ST alternatives – for example, rubber tracks are lighter, provide greater BLAST and fire resistance, and offer enhanced durability.

Up to a point, though, the long-standing popularity of ST vehicles makes sense. Tough and durable, the alloy provides excellent traction over dirt and other loose surfaces. Yet, ST comes with a number of problems – most notably around maintenance.

Fixing sophisticated ST tracks can be time-consuming. From replacing pads to retorquing end connectors, ST can render over 20% of an army’s fleet inoperative at any one time. Given that ST typically have a lifespan of around 1,500km, moreover, troops will likely have to perform three such operations during a vehicle’s service.

Just as importantly, the problems of ST can limit the range and performance of vehicles in the field. Currently, Robotic Combat Vehicles (RCVs) theoretically allow militaries to cover large distances without putting soldiers in the firing line. However, their limited lifespan means that STs risk stranding RCVs far from base, which in turn increases the vulnerability of the engineers that are deployed to recover them. At the same time, ST maintenance can be very time-consuming, and the heavy replacement pads (weighing up to 30% of the track’s weight) can be hard to integrate into mobile forces.

As a result, the costs here – in terms of manpower, equipment and operational capabilities – can be considerable. This is just one of many challenges concerning ST. Another example is related to BLAST protection – an ST that’s exposed to either mine or IED BLAST can explode and produce secondary projectiles, increasing the chances of battlefield casualties. However, as CRT is predominantly made from rubber, these types of explosions won’t turn tracks into dangerous secondary shrapnel projectiles, but simply deform and absorb the shock from the BLAST.

If Soucy’s CRT is penetrated by a ballistic attack, the very high pressure of the rubber structure means any BLAST holes will essentially self-seal as the rubber expands to fill the void – with ST, ballistic impact can result in pin fracture failures or damage bushings.

Low maintenance

With these limitations in mind, CRT presents itself as an obvious alternative to ST. First entering service on military vehicles in the late 1980s, around 70% of new Armoured Vehicle Programmes (within the weight category 10-45mT) are now being fitted with CRT.

In large part, this dramatic transformation is down to the design of CRT itself. As the name implies, CRT isn’t entirely made of rubber. About half is, with the rest formed of steel, plastics, and composite fabrics. This inherent malleability means CRT can be conceived as a single-piece technology, with the entire track boasting a unified and continuously cased rubber structure.

All of this directly translates into how CRT is maintained. Lacking the pads and connectors of ST alternatives, the only ‘maintenance’ CRT requires are visual checks before and after use.

According to a 2018 study by the British Army, trialling CRT on its Warrior tracked armoured vehicle, investing in CRT can save over 415 man-hours of maintenance work per vehicle across its lifecycle, an advantage compounded by the fact that CRT can survive on average 5,000km without being replaced. When track replacement is required, the research suggests that CRT can be replaced in less than half the time of ST, allowing RCVs and other military vehicles to fulfil operations with a much-reduced logistical footprint.

Data obtained during the 2018 trial proved that CRT is 87% less likely to lose a track than conventional ST due to being fitted at between 30–50% higher tension than conventional ST.

Cultural shifts

CRT is combined with a range of strengthening techniques – carbon nanotubes, carbon fibre and steel cords – to make it robust enough to withstand battlefield conditions. Even so, it’s a developing technology, and is yet to fully mature. As far as maintenance is concerned, for instance, as a single-piece technology any damage CRT undergoes can be more time consuming to fix than with modular ST – requiring the entire track to be replaced, rather than individual steel plates.

However, track changes rarely occur in the heat of battle – instead, maintenance work is usually scheduled well ahead of time – meaning that this benefit ST has over CRT seldom comes into effect. Both ST and CRT vehicles can easily be towed to safety if their tracks are rendered inoperable, at which point engineers can replace them at speed.

Then there’s the question of cost. At the moment, CRT can be slightly more expensive than steel alternatives in the first instance – but from low maintenance to better reliability, there’s increasing evidence that switching to rubber can reduce the life cycle costs. The future seems bright for the latest development in continuous track, to say the least.

Our media partner

Defence & Security Systems International (DSSI) was created in 1986 by retired Brigadier Gerald Blakey to address the challenges faced by the forces in terms of deployment and technology being used in the field. The magazine has evolved into one of the strongest publications endorsed and supported by senior officers, both in the field or retired, discussing the applications of the systems and platforms that are currently in operation. The publication also analyses a number of programmes that have funding from various governments and their route to theatre. Editorial contributors in this area include: the MoD, the DoD, the European Defence Agency, Dstl, the US Marine Corps, DE&S (Abbey Wood) and the US Navy. Over the last 25 years, the magazine has become required reading for over 50 defence agencies globally and their main prime contractors.

Defence & Security Systems International allows you to build brand awareness within the defence domain. The three platforms we produce are designed to allow you to communicate directly with the defence market, and, more importantly, putting defence agencies and tier one contractors in touch with advertisers.

Defence & Security Systems International delivers essential intelligence and specialist information on the latest projects, technical and product developments. It enables individuals actively involved in the purchasing of equipment and services to make informed decisions.

Produced in print and digital formats. Web portals are utilised by the international procurement departments that are directly responsible for the majority of defence and homeland security systems spending worldwide.

https://www.defence-and-security.com/

To contact DSSI: